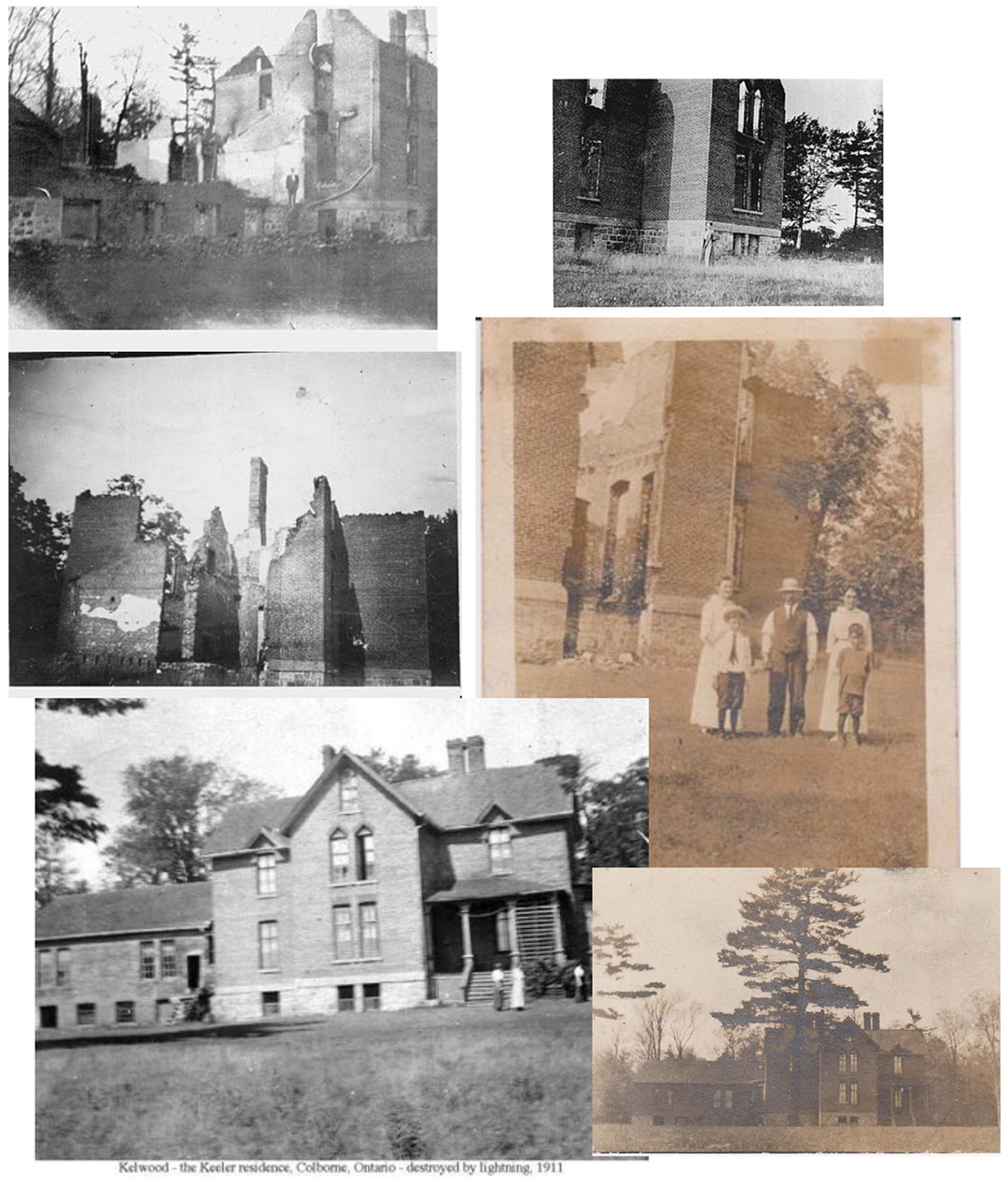

The Kelwood Story

HOUSE ON THE HILL

by Walter Luedtke

Kelwood was the “Great House on the Hill” overlooking Lake Ontario and the village of Colborne. Village founder, Joseph Keeler, built it for himself in the 1850s. It is difficult to determine just when it was built, but Mrs. Heatherington, who knew the building in her youth, says that it took the best part of twenty years to complete the house, the wings and the grounds.

In Kelwood’s heyday, the visitors’ buggy would enter the estate through a gate on Percy Street, proceed through the park and approach the mansion in a fine flourish from the west. The buggy would stop under a covered carriageway, similar to the one in the “White House” in Brighton. The n the visitor would mount a short flight of steps and enter.

Passing through a small vestibule, the visitor would enter the octagonal hall, the centre core of the building. The two foot thick brick walls rose from the basement right to the attic. On the ground floor, tapered floorboards, alternating light and dark wood, radiated from a centre plaque. A thick glass ceiling on the second floor level allowed the light from the skylight to illuminate the hall.

To the south of the building, the parlour’s eight foot windows had a commanding view of the surrounding countryside. To fight the chill winds off the lake in winter, the parlour had an enormous fireplace of green marble.

To the east, the drawing room was the most sumptuous room in the entire building. From its 15 foot ceiling a bronze chandelier cast its light over gilded ebony furniture and Victorian knick- knacks. The centre of the room belonged to a large ebony table with a marble top. Keeler’s three daughters probably played the ebony grand piano. The black marble fireplace consumed 4 foot logs.

The dining room to the west, had less of an undertaker’s atmosphere. The room was panelled in walnut throughout and contained a regal dining room table. The kitchen that supplied it, was to the north, next to the entry. Here the cook and the maids were busy around a huge stove.

Frescoes decorated the walls of the centre hallway and the staircase. Painted by the Reverend Dowling, Colborne’s first Baptist minister, they showed autumn and winter scenes, animals and soldiers on horseback. Descending the stairway one followed the course of a river flowing over rocks. The centre piece of that fresco was a soldier, wearing helmet and breastplate, mounted on a rearing horse.

The servants lived in separate quarters, in a wing to the west of the house. The ground floor held the stables and the carriage shed.

From the house, walkways and bridlepaths led past venerable old trees into park like woods. Walnut, maple and pine trees had been cut down to build the house, but there were plenty left. In a clearing, springs fed a large pond which was used for skating parties in the winter.

The last Keeler to grow up and live in all this splendour was Joseph Keeler III, the grandson of the UEL refugees who had landed on the pebble beach in Lakeport at the end of the 18th century. Little Joe as he was known due to his diminutive stature, edited and published the Colborne Transcript and was elected to Parliament in the years 1867-1874 until his death in Ottawa on January 21, 1881. He was the only son of Joseph (Abbott) Keeler, so Kelwood passed from the Keelers into the hands of the wealthy William McNeal, who was present in the house when disaster struck in the summer of 1911. Apparently during a fierce thunderstorm, the house was struck by lightning and was set ablaze. According to local folk lore, it was the carriage way that was hit and the fire quickly spread through the woodwork inside.

By the merest coincidence, the fire was discovered by Dr. Alyea, the Colborne veterinarian, who was driving with a companion down Percy Street near midnight. Dr. Alyea raced up the steep hill and roused Mr. and Mrs. McNeal and and their guest Mrs. Earl. The Earl children slept in the upper bedrooms and it proved impossible to bring them down the centre stairway. No ladder could be found to reach the upper windows and the rescuers had to improvise, typing two short ladders together with their handkerchiefs. By this device the children reached safety. At dawn the house was a scorched shell with only the massive walls jutting into the sky. The ruin became a favourite picnic spot and many a Colbornite, who had never set foot in the house, had his picture taken in front of the ruin.

What happened to the gaunt walls of Kelwood? The answer is found in the following advertisement in the Colborne Express on September 8, 1919. It reads “Brick for sale, good second hand brick. Estimate 100,000 for building purposes. On Kelwood or it could be shipped to purchaser. G.E.R. Wilson. Kelwood’s stately trees went the same way. Wilson also had for sale “200,000 square feet of 60% White Pine and Spruce. Others Maple, Ash, White Oak, Elm, Beech and Cedar. Level plateau, no underbrush on Kelwood”.