The Schuyler/Goslee Family

In 1900, Emma Augusta Currie published a book entitled “The Story of Laura Secord and Canadian Reminiscences.” A romantic account appears in her book explaining how the parents of early Colborne businessman James D. Goslee (1794-1865) first met during the American Revolutionary War. Ever since its publication the story has been bouncing around Colborne and Cramahe Township in one form or another. Currie’s is the most detailed version. Bear in mind, however, that “detailed” is not the same thing as “accurate.” Currie transcribed the reminiscence of James Goslee’s daughter Elizabeth Grover (1818-1903), who had heard the story from her grandmother. This makes it a transcription of a story told by a 72 year old woman that had been related to her by a woman who died 50 years before about events that occurred 73 years before that. If the facts became a bit garbled over that time, it wouldn’t be surprising.

How does the story mesh with historical fact? First, here is Mrs. Currie’s text:

Mrs. Grover describes the scene where her grandmother, seated on the fence under a cherry tree, saw her father and brother, with a company of volunteers, march to their last battle, and heard her brother’s parting words, “Look out you don’t fall, Sis!” Through the afternoon, from this position, she listened to the boom of the cannon, and saw their defeat. She then ordered a coloured man, their slave, to saddle two horses and secrete them, until needed, in a hickory grove nearby. Her friends were rushing past, telling everyone to save themselves, for the British were victorious and burning their homes and driving off their cattle. They saw the burning barns and knew their homes would soon follow. Her father’s last letter had told that her uncle, General Schuyler, was stationed in the Jersey woods. With her attendant she rode night and day to put herself under his protective care. While passing through a wood on the second day they saw tents in the distance, and hurried on till stopped by a sentry with the command, “Dismount.” The girl was suspected of being a spy. She stood on the ground and began to tell her pitiful story, while the slave was trying to disengage an enormous horse pistol from his garments. Just at that time a young officer came riding up, and she noticed that his red coat showed one sleeve gone, and the place supplied by a blood-stained bandage. She knew at once that she was in the enemy’s camp, with the evidence of battle surrounding her. She was weak and faint for want of food, and wearied with her long ride. The officer sent for food and wine, and told the coloured man to put up his pistol, “for the young lady will come to no harm. Is she your mistress, and who is she?” he asked. “Yes, massa, she is my mistress, Miss Annie Schuyler. The Britishers have killed my massa and Mr. Philip, then burn us up, and we run away to find my missus’ uncle. We thought he was in these woods; guess we’re mistaken.” “My God!” exclaimed the officer, ”a niece of General Schuyler in this wood with no protection but this slave!” He begged her to take the food. When she had done so he assisted her to remount her horse, and, leading the way, gave the necessary directions, following which, a few hours after, she found herself with her uncle at his headquarters. From there she was sent to the old Schuyler mansion near Albany, and remained with her cousins until her marriage, which was from his house and with his approval. It was there she again met the officer who had shown her such considerate kindness in those hours of bereavement, defeat, and danger.

Scarlet riding-habits were the fashion of that time. The one worn on this memorable day was afterwards made into a cloak with a chapeau, long used during her Canadian life, and the saddle is now in Mrs. Grover’s posession. Matthew Goslee was the name of this brave man, who afterwards became her husband. His family lived in Maryland, and six brothers served in the Continental Army. He served under Cornwallis, and was in the 33rd Foot, participating in many battles of the Revolution. He was with Cornwallis in his unfortunate campaign, and was among those who gave up their swords at the surrender at Yorktown, October 11th, 1781. He ever referred to this as the most unhappy day of his life.

Mr. Goslee owned a plantation and fifty slaves. These were confiscated at the close of the war. The plantation was bought in by his brothers and offered to be restored if he would return and live there. He chose, however, the life of the Loyalist along with his faithful wife, Ann Schuyler.

James D. Goslee’s parents were Matthew Goslee (1757-1830) and Ann Schuyler (1762-1850), the young people described in the story. In her book, Mrs. Currie also quotes Ann’s obituary in the Colborne Express, 1850, which repeats the assertion that Ann Schuyler Goslee was the niece of “General Schuyler of Revolutionary fame” (Major General Philip Schuyler, 1733-1804). The obituary also states that Ann was born in Albany, New York, and that she accompanied her husband to Canada in 1783. Mrs. Currie also mentions that “Mrs. Grover copies from an old register the following marriages”, one of which states that ”the marriage of Ann, niece to General Schuyler, at the old Mansion House in Albany, to Matthew Goslee, a soldier of the Revolution, took place on the 11th of August, 1782.”

That is all that Mrs. Currie has to say about the early history of Matthew and Ann Goslee. Another published version of the story, in Eileen Argyris’ “How Firm a Foundation” (2000), says that George Washington himself was Ann’s Godfather and that he often visited the family home near Albany, New York. This version has Ann “alone in a house near Albany” when she heard the sounds of battle approaching. Her mother had recently died and there was a chance her father and brother had been killed in the fighting. She saddled her horse and rode off in search of her uncle, the General. There is no mention of the slave companion. Also in this version, the redcoat she meets (Matthew Goslee) was “tall [and] handsome”. These details were from an article in the Colborne Chronicle from 1962, entitled “I Remember” by Jim Bell.

Margaret McBurney and Mary Byers tell a similar story in “Homesteads: Early Buildings and Families from Kingston to Toronto” (1979), except this time they give an exact date for Ann’s setting off in search of her uncle: 27 August 1776. The slave companion is back in this version. Ann’s second meeting with Matthew is specifically placed when he is brought to General Schuyler’s house in Albany as the General’s personal prisoner.

Unfortunately, there are problems with some of the details in this story.

First, I can find no niece of General Schuyler named Ann. His parents Johannes Schuyler, Jr. (1697-1741) and Cornelia Van Cortlandt (1698-1763) had 10 children: Gertrude (b. 1724), Johannes (b. 1725), Stephanus (b. 1727), Stephanus (b. 1729), Philip (b. 1731), Philip (b. 1733; the General), Cortlandt (b. 1735), Stephanus (b. 1737), Elizabeth (b. 1738), and Oliver (b. 1741). If Ann Schuyler was the niece of General Philip Schuyler, one might expect that she was the daughter of one of his seven brothers or of his sister Gertrude, who married a Peter Schuyler.

Johannes, the first two brothers named Stephanus, the first Philip, Oliver, and Gertrude’s husband all died before Ann was born. Cortlandt lived long enough to have been Ann’s father, but not long enough to have been involved in the Revolution: he died in 1773. Besides, his children were named Sarah (b. 1764), Van Cortlandt (b. 1769), John (b. ca. 1770), Francis (b. ca. 1771), and Cornelia (b. ca. 1773), not Ann. The third Stephanus (often referred to as Stephen) also lived long enough (until 1820) and he served in the New York Militia during the Revolution. He’s not a perfect fit to the story, though, because Stephanus married Lena (or Helena) Ten Eyck (1745-1818) in 1763, the year after Ann was born. Also, Stephanus and Lena had 10 children, none of them named Ann (Johannes b. 1764, Tobias b. 1766, Philip b. 1768, Tobias b. 1770, Henry b. 1772, Philip b. 1775, Cornelia b. 1777, Barrent b. 1780, Stephen b. 1784, and Cortland b. 1786).

No alternative explanation for Ann’s identity seems apparent either. None of the nieces of General Schuyler could be mistaken for Ann, even if “Ann” was an alternative name for one of them. In terms of age only Sarah, daughter of Cortlandt, comes close, but she was two years too young and had no brother Philip. Besides, Cortlandt’s wife Barbara moved with her children to Ireland after his accidental death in 1773 when he fell from a horse. Tracking all of the descendants of the General’s great grandfather, it turns out that the General had four relatives named Ann, Anne, or Anna, but none of them match our Ann. One was his grandfather’s sister Anna, who died in 1698. Second cousin Ann, granddaughter of the General’s great uncle Brant, was born in 1752 and married John Bleeker. The other two were the children of the General’s second cousins, both of them great-grandchildren of the General’s great uncle Arent: Anna was born in 1770 and married John Schuyler; Anne was born in 1776 and died in 1783 at the age of seven. Our Ann wasn’t the niece of General Schuyler’s wife either; there was no Ann among them, and she would have had the last name Van Rensselaer anyway, if that had been the connection.

Another weak contender for Ann’s father, because he was in the New York Militia, was Philip P. Schuyler (1736-1808), a brother-in-law of the General’s older sister Gertrude. Such a relationship might have led his daughter to refer to General Schuyler as “uncle”. However, there is no record of this Philip Schuyler having a daughter Ann or a son Philip, and all of his recorded children were too young to be confused with Ann, the oldest having been born in 1766).

Finally, one genealogy on Ancestry.ca actually lists parents for Ann Schuyler: Philip Schuyler (1743-1811) and Rebecca Ryerson (1741-?). However, Philip and Rebecca were from New Jersey, not New York, and Philip was only distantly related to General Philip Schuyler: his father was the General’s second cousin. It seems unlikely that Ann would have referred to her grandfather’s second cousin as “uncle”. Besides, two other Ancestry.ca genealogies list the daughter of Philip and Rebecca as Anna (b. 1793), who married Morris Beam (1799-1852) in New Jersey, or Annatje (b. 1763) who married Richard DeGraw (1755-1841) also in New Jersey.

So I can find no record of an Ann Schuyler being the niece of General Schuyler. Yet it’s hard to believe there isn’t something to the story. It is just too detailed to have been simply made up. There is even a reference in Mrs. Currie’s book to a visit from General Schuyler’s youngest daughter Catherine (1780-1875) to Ann. Catherine was Mrs. Cochrane at the time and living in Oswego, New York. Since James Cochrane (1777-1858) was Catherine’s second husband, and since her first husband died in 1817, the visit must have occurred sometime after that date. Ann had been resident in Cramahe Township for many years at that point. Why would General Schuyler’s daughter visit Ann in Canada if there wasn’t a close connection?

It may be that Ann Schuyler was General Schuyler’s niece in a biological, but not a legal, sense. Perhaps she was the illegitimate daughter of one of the General’s brothers. If so, the best candidate would have been his younger brother Stephanus, although he doesn’t fit the story perfectly. Perhaps it is more likely that she was the daughter of an illegitimate son of the General’s father. This would mean that the General had a brother who doesn’t appear in the published family genealogies. Such a relationship might help explain why the daughter of a well-to-do and very influential Albany family might have willingly headed off to the wilds of Canada and why her family might not have objected to her doing so.

The second problem arises when one looks at the military actions in upstate New York during the American Revolution. One version of the Ann Schuyler story has her hearing the sounds of battle approaching her house near Albany. The only times the British invaded upstate New York were in 1776 when they chased the Americans out after their failed attempt to invade Canada, and during the Summer of 1777, when the British mounted a full-scale invasion. In neither case did the British get anywhere near Albany.

General Schuyler, although originally in command of the attempted invasion of Canada in 1775, was invalided home early in the campaign with “rheumatic gout”. He didn’t return to upstate New York until July of 1776, when he arrived at Crown Point on Lake Champlain.

Until October of that year, the British were kept from moving south from the head of Lake Champlain by the American dominance on the lake. Although General Schuyler and the British forces were both located in the Lake Champlain area in the late summer of 1776, troop movements were on the lake rather than overland, so the events in the Ann Schuyler story couldn’t have occurred there. Besides, the area was pretty much wilderness at the time, so the presence of a Schuyler house in the area, complete with slaves, seems unlikely.

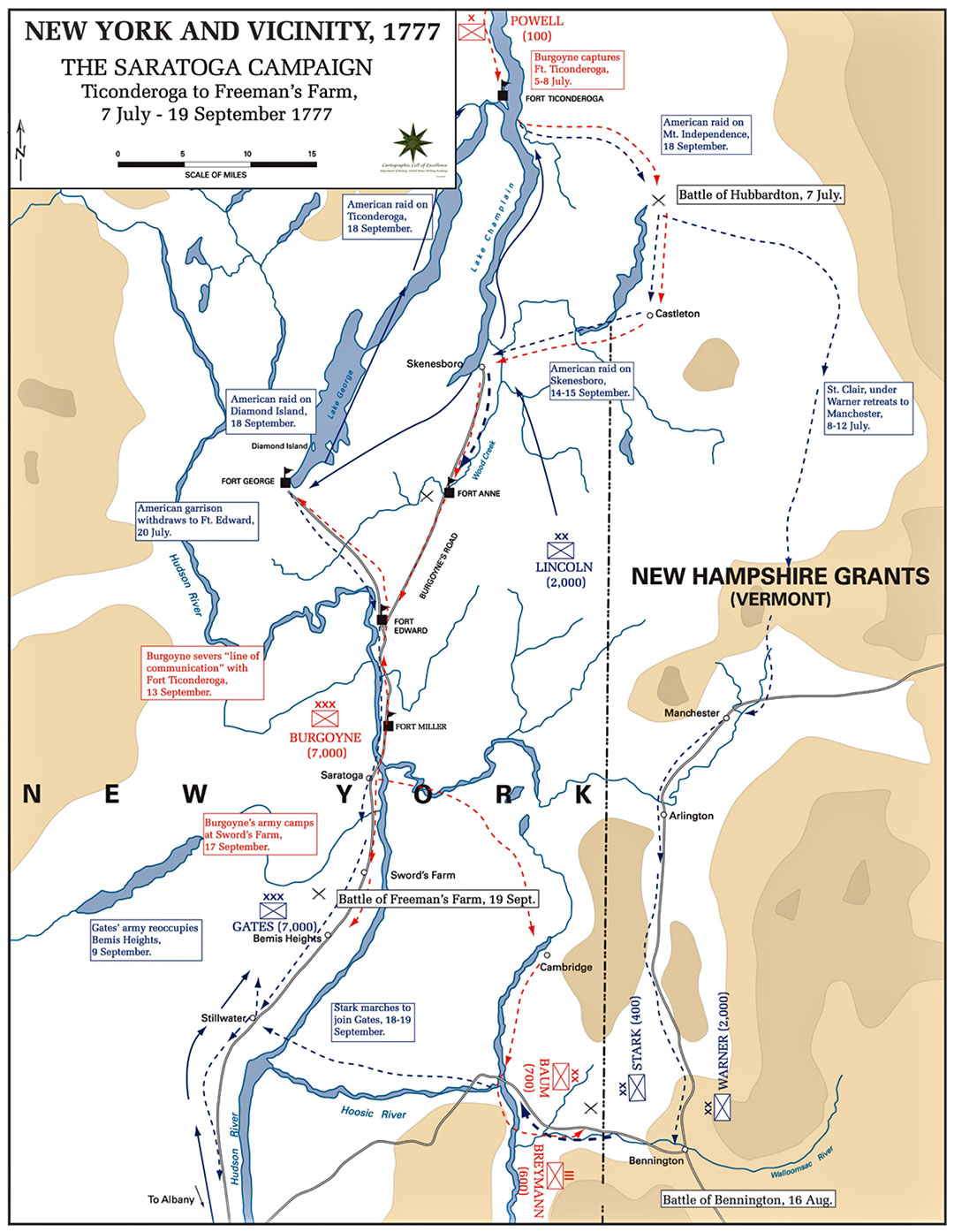

A British incursion much more deeply into New York occurred in the summer of 1777. The British plan was for a three-pronged attack, one down Lake Champlain and the Hudson River from the north, one down the Mohawk Valley from the west, and one up the Hudson from the south. The idea was for the three prongs to meet at Albany and thus cut New England off from the other colonies. The western prong under Colonel Barry St. Leger was stopped by Benedict Arnold at Fort Stanwix, 178 km from Albany. The southern prong never even got started: General William Howe decided to capture Philadelphia instead of following through with his part of the invasion plan. The northern prong under General John Burgoyne, after successfully capturing Fort Ticonderoga on Lake Champlain, was defeated at the Battle of Saratoga, about 50 km north of Albany, in October 1777.

So there never were any “sounds of battle approaching Albany”, as related in the Ann Schuyler story.

If we put the fact that we can’t find our Ann in the Schuyler family on the back burner for the moment, is there any way we can make the rest of the story mesh with known historical facts? The only “sounds of battle” anywhere near Albany were 50+ km to the north between the British capture of Fort Ticonderoga on July 5 and British surrender at Saratoga on 17 October 1777. Perhaps the events in the story actually occurred there instead of at Albany. For that to be the case we would have to be able to place Ann Schuyler, Matthew Goslee, General Schuyler, and Ann’s father and brother there during the battle.

Let’s look at the simplest part of this first: was General Schuyler there? Yes. When the British launched their invasion campaign into upstate New York, Schuyler was active in preparing for the defense of the colony and his headquarters were in the field for several weeks. However, he was accused of dereliction of duty when Fort Ticonderoga was surrendered to General Burgoyne in July, and was replaced by General Horatio Gates part way through the campaign. Although he was later vindicated by the court martial he demanded, he resigned from the Army in April 1779, after which he served in the Continental Congress.

Gates arrived on the field to replace Schuyler on 19 August 1777, at which point Schuyler went to Albany. He didn’t return to Saratoga until after the British surrender, at which time he offered to provide Burgoyne with lodging in his own house in Albany while Burgoyne was a prisoner.

See map. Between 5 July and 21 July, Schuyler’s camp was at Fort Edward. From 21 July until 3 August he was at Moses Creek (the creek on the east side of the Hudson just north of Fort Miller on the map). He then crossed the Hudson at Fort Miller and camped at Stillwater until he was replaced by Gates on the 19th.

Where were the British during this time? They captured Ticonderoga on 5 July, and by 8 July were mostly at Skeensboro, though advance parties had reached as far as Fort Ann. Reconnoitering continued as far as Fort Edward until 29 July, when the British took that Fort. Burgoyne himself arrived at Fort Edward on 31 July. By 9 August the British, still mostly at Fort Edward, had an advance camp as far south as Fort Miller. They remained at Forts Edward and Miller until 11 September, after Schuyler had left the field, and so after the period of interest to us.

Somewhere among these troop movements the events in the Ann Schuyler story may have occurred.

Was Matthew Goslee present at Saratoga? Mrs. Currie places Matthew in the 33rd Foot. On the other hand, Empire Loyalist land grant documentation lists Sergeant Matthew “Gosley” as having been in the Prince of Wales Volunteer Regiment. Was Mrs. Currie wrong? Were there two Matthew Goslee/Gosleys? Was Matthew Goslee in the 33rd Foot in 1777 and later transferred to the Prince of Wales Volunteers?

I think there is no doubt that our Matthew Goslee was, at least at the end of the war, in the Prince of Wales Volunteers. Presumably he himself provided that information when applying for land in Canada after the war. Also, muster rolls for that regiment list Corporal Matthew “Gosley” as present in Charlestown, South Carolina, between April and June 1781. Finally, Corporal Matthew “Gosley” was listed as serving in the British Legion under Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton when he was taken prisoner on 19 October 1781. Mrs. Currie’s story states that Matthew was present when Cornwallis surrendered to Washington at Yorktown, Virginia. As it turns out, Cornwallis surrendered on 19 October 1781, the same day the Goslee was captured. The British Legion is known to have received reinforcements from the Prince of Wales Volunteers, and Matthew was presumably among those reinforcements. If so, he didn’t actually surrender at Yorktown per se. Rather, he surrendered across the York River at Gloucester Point.

So in 1781, Matthew Goslee was in the Prince of Wales Volunteer Regiment in the Carolinas and Virginia. But where was he in 1777? Was either of the regiments in question present at Saratoga?

Although most of the 33rd Foot was absent, two companies under Lt. George Nutt were indeed handling artillery at Saratoga and were captured with Burgoyne. Similarly, the Prince of Wales Volunteer Regiment, as such, was not present at Saratoga. However, two officers, Gershom French and Francis Hogle, who had been busy recruiting for the Volunteers in Connecticut, led a contingent of men from there to join Burgoyne. Many of these men fell out along the way, but the remainder were placed into the Queen’s Loyal Rangers by Burgoyne and were present at Saratoga. It is possible that Matthew Goslee, recruited for the Prince of Wales Volunteers by French and Hogle, was among these men serving at Saratoga under the Queen’s Loyal Rangers, and that after his capture and parole(?) he eventually made his way back to the Volunteers where he stayed for the remainder of the war. It is also possible that he was in the 33rd Foot and transferred to the Prince of Wales Volunteers after his parole.

Circumstantial evidence weakly (very weakly) suggests that the Prince of Wales Volunteer theory might be a bit more likely:

- The 33rd Foot was a British regiment while the Prince of Wales Volunteers were American Loyalists. As a rule, Loyalist Americans, such as Matthew Goslee, preferred joining Loyalist American regiments, so one might think that Matthew would be more likely to have been associated with the latter regiment. However, British units did accept American recruits when they were available.

- The Prince of Wales Volunteers were recruited largely from Fairfield County, Connecticut, beginning in the early part of 1777. Is there any reason Matthew Goslee would have been in Connecticut at that time? Not that I can find. There were Goslees living in Connecticut then, but I can’t find any clear relationship between them and Matthew’s family in Maryland. However, neither do I have any reason to think he wasn’t in Connecticut in 1777.

- The Queen’s Loyal Rangers were used as scouts in front of the British forces at Saratoga. The only members of the 33rd Foot present were two artillery companies. It seems a bit more likely that Ann Schuyler would have met a member of a scouting party than a member of an artillery unit.

I suppose it is possible that both theories are partially correct. Although the Prince of Wales Volunteers were placed under the Queen’s Loyal Rangers, there could potentially have been some temporary transferring of troops on the battlefield so that Matthew Goslee was in fact briefly serving with the 33rd Foot when he met Ann Schuyler. This, of course, is complete speculation and seems a bit of a stretch. But where would Elizabeth Grover (quoted by Mrs. Currie) have gotten the idea that Matthew was in the 33rd Foot? Overall it was a very famous regiment (later known as the Duke of Wellington’s Regiment), but it was certainly obscure with regard to British actions at Saratoga.

The Prince of Wales Volunteer Regiment and Empire Loyalist land grant documentation lists Matthew’s rank as corporal in 1781 and sergeant after the end of the war, not “officer” as in the Ann Schuyler story. Since we don’t know for sure what regiment he served with at Saratoga, we don’t know his rank at the time, but if he was still a corporal by the surrender at Yorktown, it is unlikely that he was an officer four years earlier, presumably shortly after first enlisting.

Regarding Matthew’s origins, Mrs. Currie says that he was the son of a wealthy family in Maryland and had six brothers who fought in the Continental Army, Matthew siding with the British. Matthew’s great-grandfather John Goslin (or Gosling) (ca. 1655-1721) was, in fact, among the early settlers of Somerset County, Maryland, and I have seen a reference to Matthew’s uncle, at least, being a wealthy slaveholder. So it is probably true that Matthew’s family was well-off as well. I have found references to only five brothers rather than six, and I don’t know yet whether they served in the rebel forces during the Revolution, as in the story. But there apparently were Somerset County Goslees who were “patriots”, so I have no reason to doubt the story. Mrs. Currie goes on to state that Matthew owned a plantation with 50 slaves. Matthew was the fifth of the six sons in his family, and his father, John Goslee (ca. 1730-1795) was still alive during the war, so it is unlikely that Matthew owned this plantation. His family probably did, but not Matthew himself. If this is true, and if his brothers did fight for the rebels, the story about the confiscation of the plantation is probably inaccurate. But then, perhaps he did own a plantation himself. Maybe all of the brothers owned property on their own. I don’t know.

We don’t know who Ann was, but the story places her at the family home listening to the sounds of battle approach. Was there as Schuyler house in the area? Absolutely. In 1740, 12,000 acres of land extending south along the Hudson from Fort Edward were granted to John and Philip Schuyler, among others. This was known as the “Schuyler Patent”. “John” was Johannes Schuyler, the General’s father, and Philip was his uncle, killed five years later in fighting with the French and Indians. Thereafter the Schuyler family was very prominent in the area, and in fact the town of Saratoga was renamed Schuylerville in 1831 in their honour. General Schuyler had a country home there that was burned by the British on 10 October 1777, after the final battle of Saratoga but before the British surrendered.

Two of the three versions of the story have Ann accompanied by a slave. A slave in New York? Yes indeed. Many well-to-do families had slaves in New York in the 18th Century, and the Schuylers were no exception. In fact, slavery wasn’t outlawed in the state until 1827, just 36 years before Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation outlawed it in the rebel states during the Civil War.

Were Ann’s father and brother present during the Saratoga campaign? Without knowing for sure who her father was, we can’t answer this. However, as outlined above, a possible candidate for her father was the General’s brother Stephanus (or Stephen). He was indeed present, as colonel of the 6th Regiment of the Ten Broeck Brigade of the Albany County Militia. The Currie version of the story has Ann’s brother Philip accompanying his father. Stephanus’s son Philip was only 2 years old at the time, so obviously wasn’t present. However, this oldest son Johannes was 13 and could conceivably have been with his father during the campaign. If there was another, perhaps illegitimate, brother, it would not be at all surprising if he was involved as well, especially if he had a home in the area. Unfortunately, complete records of American combatants do not exist.

Given this information, we can pin down the likely date of the story a bit more accurately. Ann’s home was probably somewhere in the Schuyler Patent, between Fort Edward and Saratoga. Advance units of the British reached Fort Edward on 21 July. As far as I can tell, they remained east of the Hudson until September. There is no indication in any version of the story that Ann had to cross the river to reach her uncle, so the story probably took place before the General crossed on 3 August. Between these dates, General Schuyler’s headquarters were on Moses Creek. Since both armies were on the eastern side of the Hudson, Ann’s home must have been on that side as well. Although skirmishing as far south as Fort Edward by 21 July, the British didn’t actually take the fort until 29 July. This suggests that there wasn’t much action south of Fort Edward before that date. The American army abandoned Fort Edward on the 28th, and joined General Schuyler at Moses Creek. For Ann to have been led from a British camp directly to General Schuyler’s camp without running into other American forces in between, it would seem most likely that the event occurred after the 28th. This places the first meeting of Ann Schuyler and Matthew Goslee in the last couple of days in July or the first couple of days in August, 1777. This doesn’t jibe with the date of 27 August 1776 in the McBurney and Byers version of the story, but, as I have pointed out, the British were restricted by the American Navy to the northern end of Lake Champlain at that date so it can’t be accurate.

So, if we adjust a few details of the Ann Schuyler story, we can actually make it work quite well. Here is my working hypothesis:

Ann Schuyler was the niece of General Schuyler, likely the daughter of an illegitimate brother. This hypothesis of illegitimacy allows us to be able to accept the story’s details that her mother was dead and that her father and brother were fighting the British, and perhaps killed. These facts don’t fit if we try to squeeze Ann in as the daughter of one of the General’s legitimate brothers. The illegitimate nature of the relationship also makes it unlikely that George Washington was Ann Schuyler’s godfather. However, notice that the association with George Washington did not appear in the Currie version of the story, the one that came most directly from Ann Schuyler through her granddaughter.

Sometime within a couple of days one way or the other of 1 August 1777, when she was 15 years old, Ann heard the sounds of battle approaching her house (her father’s house?) on the east side of the Hudson River in the Saratoga region, not in Albany. She and her slave headed off in search of her uncle, who was camped on Moses Creek. Her concern would have been well warranted. There were several incidents at this time of Indians accompanying the British killing local families. The most famous case was the murder of Jane McCrae (who was actually a loyalist) on 27 July just outside Fort Edward. This particular murder became very important as a propaganda tool. It fired the imagination of the American public and caused a flood of New Yorkers joining the ranks of the militia.

Famous painting of “The Death of Jane McCrae” by John Vanderlyn, 1804

Ann and her slave ran into the wounded Matthew Goslee (age 20), who was probably not an officer, serving in the Queen’s Loyal Rangers (or less likely in the 33rd Foot). The story suggests that this meeting took place in the “Jersey Wood”, but I can’t find any reference to such a place. Matthew provided Ann with food and directed her to her uncle’s camp. Whether he actually guided her there is questionable. He would have had to get permission to do so. Ann found her uncle, who sent her on to his house in Albany, where she remained for the rest of the war. The general himself followed after he was replaced by General Gates on 19 August. Matthew probably surrendered with the remainder of the British forces on 17

October after the battle of Saratoga, although he might have been captured by chance some time before that date. The story then states that General Schuyler took him to Albany as his personal prisoner, where Matthew again met Ann. For this to be true, the General would have had to have known the details of Ann’s adventure and to have been grateful enough to Matthew to actively seek him out following the surrender. I suppose it’s even possible that the General had already met Matthew, if Matthew had in fact personally delivered Ann to her uncle back in July/August. As we have seen, General Schuyler did return to Saratoga after the battle, when he made the offer to lodge the captured General Burgoyne in his Albany home, so finding Matthew would have been no problem. Matthew was later exchanged, and rejoined the Prince of Wales Volunteer Regiment, his original unit. He ended up surrendering again at Gloucester Point across from Yorktown on 19 October 1781. Matthew (age 25) returned to Albany and married Ann (age 20) on 11 August 1782. This was after the end of hostilities, but before the signing of preliminary peace articles at the end of November of that year. Matthew, a twice-captured British soldier, therefore married the niece of an American general before the war was officially over.

If this story is true, Matthew and Ann Goslee probably had some of the most illustrious acquaintances of any residents in Cramahe history. Not only did they know General Philip Schuyler (Ann’s uncle) and General John Burgoyne (a “guest” in the Schuyler mansion where Ann lived at the time), but Ann’s cousin Elizabeth was married to Alexander Hamilton, the fellow on the U.S. 10 dollar bill. In fact, Hamilton was present in Albany on 11 August 1782, and for all I know he may even have attended the Goslee-Schuyler wedding.

This discussion presents my best estimate of the events surrounding the meeting of Matthew Goslee and Ann Schuyler. Obviously, much of it is supposition built on top of supposition, and any single fact of which I am yet unaware might bring part or even all of it tumbling down. The information discussed here is gleaned solely from the internet, and obviously a lot more research could be done. The first and most obvious thing to do is to contact the Schuyler House Museum and the Schuyler Archives in Albany to see if there is any reference to Ann and her parents. Further searches of military records for Matthew Goslee might also be fruitful, as would a trip to Somerset County, Maryland.