A History of Cramahe Township Streets

The Streets of Colborne

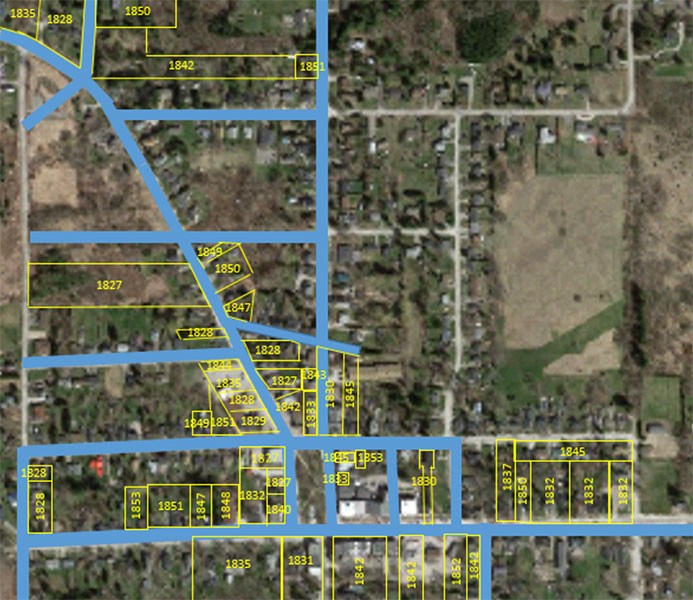

Figure 1. Modern Colborne

The only available historical maps of Colborne are found in a relatively small number of land development plans (see below) as well as in the 1878 Northumberland Atlas, a 1934 insurance map produced by the Underwriters’ Survey Bureau, and a limited number of land purchase records that include maps. Other information comes from the text of the land purchase records and from a smattering of Colborne bylaws.

The problem is that almost none of these maps can be taken as gospel. First of all, the various development plan maps were proposals for future developments and were drawn up prior to any street construction. As can be seen in the discussions that follow, some of the streets proposed in these plans probably never actually existed. Even the maps that were not part of development plans have to be taken with a grain of salt. For instance the 1934 insurance map includes several streets that no longer existed in

1934 (see below). This is also true of the land purchase maps. All of these maps appear to include all of the streets that were officially still on the books in town records when the maps were produced, regardless of whether they were still functional. Through the years bylaws have been passed officially decommissioning particular streets. This usually happened long after such streets had ceased to function, but it looks like the official land-use maps continued to show these streets until this decommissioning occurred. Unfortunately, availability of early bylaws is very spotty. Some streets seem to have simply disappeared from land-use maps, but it is suspected that bylaws for which no copies have survived had been passed to close them. Examples are scattered through the discussions below.

Although presence of a street on one of these maps doesn’t necessarily mean the street still existed when the map was produced, absence from the map is probably pretty good evidence that it had disappeared. The only other alternative would be a mistake on the part of the mapmaker.

The one map that may not fit this pattern of inaccuracy may be the one in the 1878 Atlas of Northumberland County. It appears that the intent of its mapmakers was to portray what actually existed at the time. At least no clear instances proving otherwise have been found.

The following discussion uses all of the available sources in combination to try to come up with the most likely sequence of events.

The First Colborne Street: the Danforth Road

Although the indigenous population of the area had a system of trails along the north shore of Lake Ontario, the first European-style road between York (Toronto) and the Bay of Quinte was commissioned in 1798 and completed by Asa Danforth (1768-ca. 1821) in December of 1799. Bear in mind that only six years prior to this York didn’t even exist, so the road was a very early endeavor on the part of the European settlers in the region. Also bear in mind that these settlers were few and far between. The population of York in 1799 was estimated to have been only 240 people. By comparison, the population in 2014 was 2,809,000. This is almost 12,000 modern people for every person in 1799.

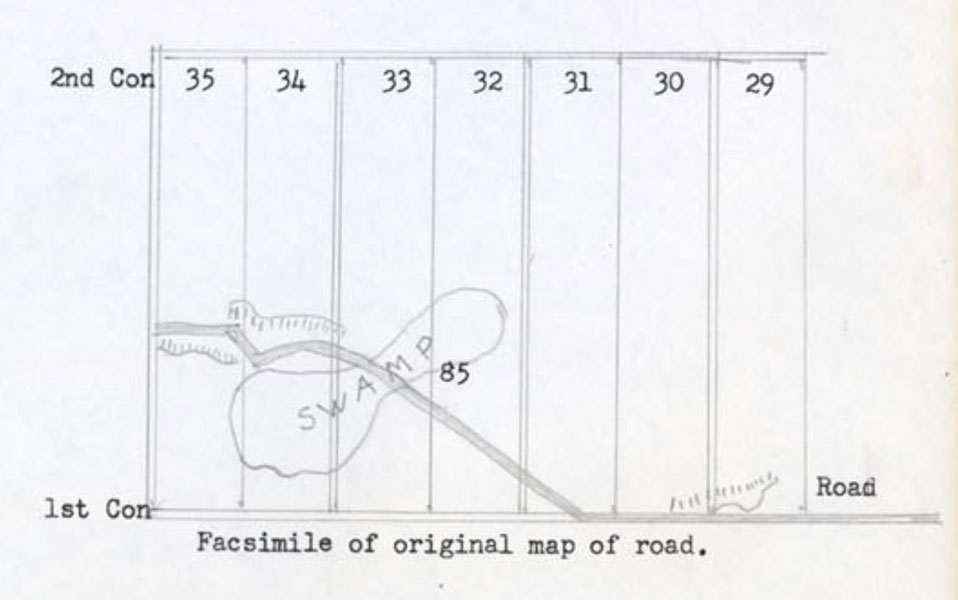

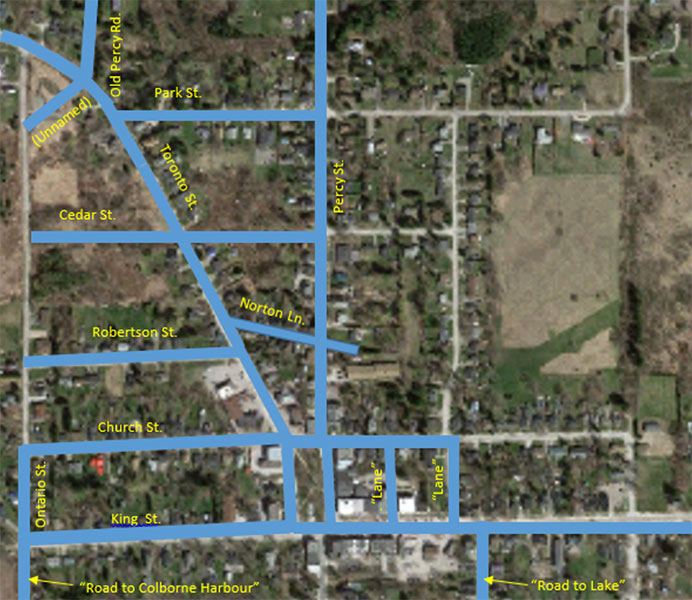

Percy Climo (1906-1991) wrote a series of articles on local history for the Colborne Chronicle when that newspaper still existed. In a 1981 entry he discussed the Danforth Road and provided a facsimile of Danforth’s original map of its route through what would later be the Colborne area (Figure 2) he also plotted that map onto a map of modern Colborne (Figure 3).

On Climo’s map, the Danforth Road leaves the route of modern Highway 2 west of Colborne and reconnects with it at about the site of the Colborne Land Registry Office. But was this really the position of the Danforth Road? It bears no resemblance to the eventual layout of the town.

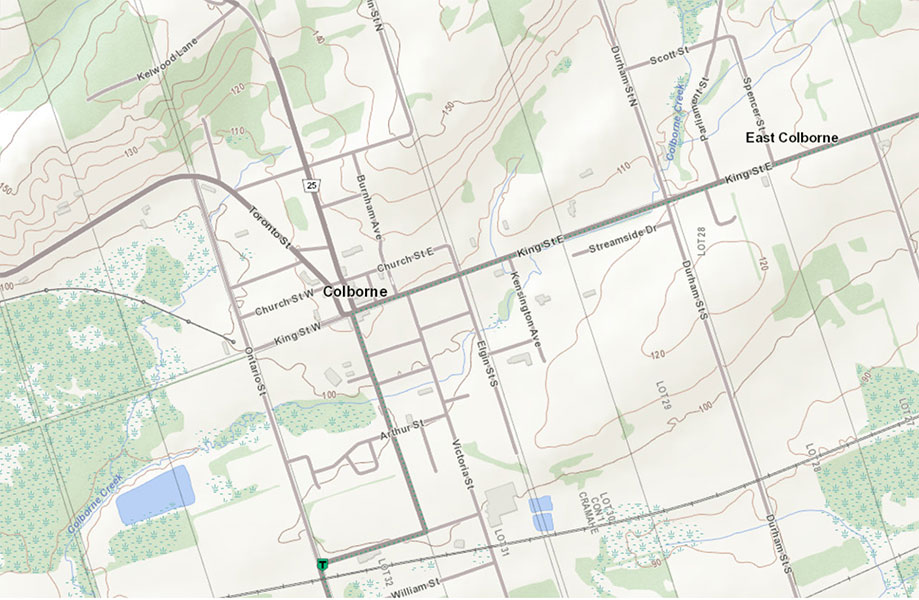

Figure 4 shows a topographical map of the Colborne area. It clearly shows the “swamp” illustrated in Climo’s Danforth facsimile (Figure 2). It is apparent from the topographical map that this wetland does not extend as far northeast as portrayed by Danforth. It can also be seen that modern Highway 2 neatly skirts the northeastern end of the wetland while Danforth’s map shows his road cutting straight across it. When one drives along this section of Highway 2 it is very obvious that the road is purposefully placed along the base of the ridge to the north, several feet above the wet flatland to the south. The modern Highway follows the route of the York-Kingston Road laid down in about 1816 and the builders of that road clearly saw the wisdom of avoiding the swamp. Since avoiding it wouldn’t have added very much total distance, it seems likely that Danforth also would have dodged this easily-avoided obstacle.

The Danforth map was produced in preparation for building the road, not after the road was already built and, according to Climo’s article, “the deputy-surveyor, in charge of the work, was permitted to

Figure 2. Climo’s facsimile of Danforth’s map

make deviations where necessary to carry the road through drier land.” It therefore seems more than likely that the Danforth Road followed the same route as the 1816 road and modern Highway 2, and not the route illustrated in Figure 3.

North to Castleton and Southwest to Lakeport

The next roads to appear in the area were probably the roads to Castleton and to Lakeport, which likely made their appearance shortly after the Danforth Road went into operation.

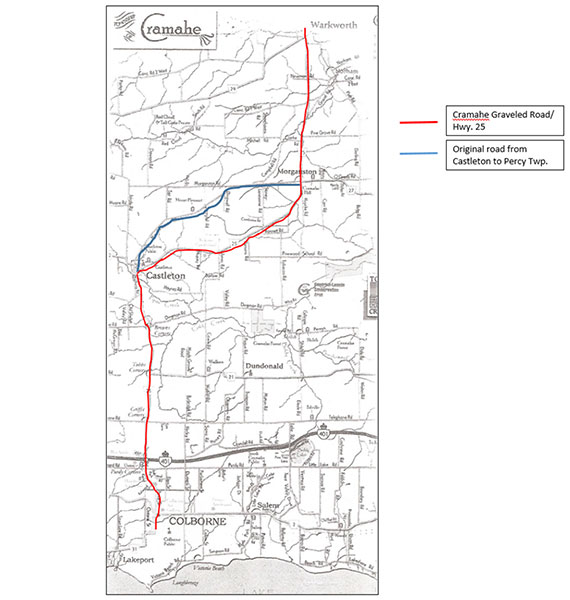

The Keelers are supposed to have built a mill at the site of Castleton in 1806. There would have been no way to transport the products of that mill except by road, so a Castleton-Colborne road probably dates from this time. This road eventually became County Road 25, but through most of its history it was referred to as the “Cramahe graveled road” or “Percy Road” since it led north beyond Castleton to what was then Percy Township and the community of Percy Mills (later Warkworth). In early Colborne the road to Castleton did not follow Percy Street as it does now, but rather it followed Old Percy Road. Most of the Colborne part of Old Percy Road was decommissioned in 1886. Only a cul-de-sac off of Toronto Street remains at its southern end (see Figure 1).

The earliest European immigrants to the Cramahe area settled around Cat Hollow, later called Colborne Harbour and then Lakeport. The Danforth Road was constructed several miles to the north of Cat Hollow. One would imagine that the residents of the lakeside community would have wanted access to this road, so it is reasonable to assume that a branch road was quickly constructed. In fact a house built in about 1806 by Joseph Keeler (1763-1839) lies along this road between Lakeport and Colborne. Modern County Road 31 from Lakeport to Colborne runs along Earl and Division Streets in Colborne, but those streets didn’t exist until the 1850’s (see below). The original route of the road to Colborne Harbour ran instead along what is now King Street West and Ontario Street.

Colborne was originally called “The Corners”. This was with reference to the junction of the Danforth Road with the Lakeport Road and with the road heading north toward Castleton and Warkworth.

From 1810 to 1854

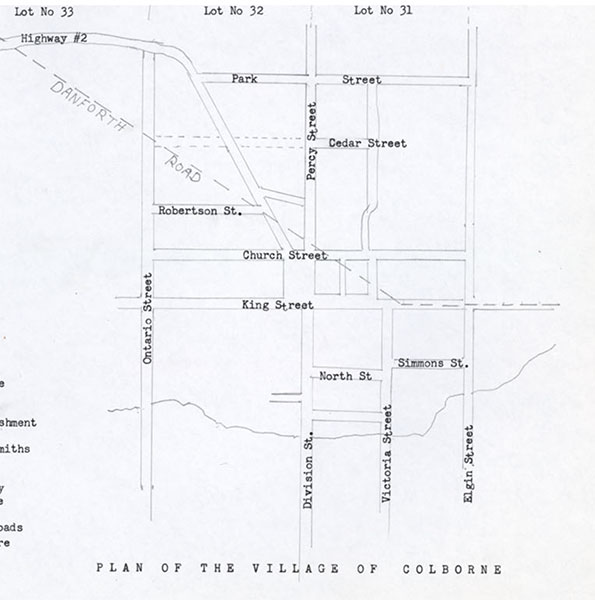

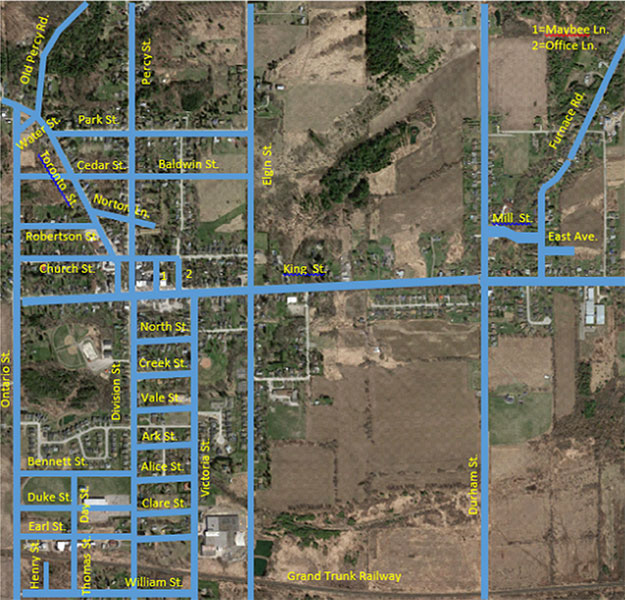

Unfortunately, no map is available for Colborne prior the Keeler Plan of 1854. Figure 5 shows the streets included on that map, overlain on the map of modern Colborne.

Figure 3. Climo’s projection of Danforth’s map onto modern Colborne.

The 1854 streets match for the most part the streets of modern downtown Colborne and the area to the north and west. But not exactly:

- Ontario Street did not exist north of Church Street and its continuation south of King Street was not called “Ontario Street”.

- There was a short unnamed street across Toronto Street from Old Percy Road, which no longer exists.

- Cedar Street extended westward to a road allowance that is now a northward extension of Ontario Street. Its western limit now is on Percy Street.

- Norton Lane extended for a short distance east of Percy Street. Modern Norton Lane now exists only between Toronto and Percy Streets.

- Maybee and Victory Lanes were unnamed in 1854.

- Church Street extended east only to what is now called Victory Lane, not to Elgin Street as it now does.

- Elgin Street did not exist.

- Division Street did not exist.

- Victoria Street was called simply “road to lake”.

Figure 4. The topographic layout of Highway 2 (the York-Kingston Highway).

The trick at this point is to try to determine when these streets came into existence. All of the streets on the Keeler map other than King Street, Toronto Street, Old Percy Road, and the “road to Colborne Harbour” were almost certainly not in existence in 1816 when the York-Kingston Road was laid down. At that time everything on the north side of King Street belonged to Joseph Keeler (1763-1839). Everything on the south side of King Street and west of where Division Street would later lie belonged to John Ogden (1765-1864), and everything south of King Street and east of the future Division Street belonged to the Crown.

Figure 6 shows all of the properties sold in this area prior to 1854, with the year of original sale for each. As of 1854 everything not yet sold on the north side of King Street belonged to Joseph Abbott Keeler (1788-1855). On the south side of King Street the unsold property west of the future Division Street belonged to Norman Bennett (ca. 1819-1872), everything unsold between Division Street and Victoria Street belonged to Joseph Abbott Keeler, and everything unsold east of Victoria Street belonged officially to the crown but functionally to the Anglican Church.

Sadly, except for an 1845 reference to Norton Lane, none of the land sale records for these properties made direct reference to a street name. Occasionally one would refer to “the road” or “the main road”, referring to what is now known as either Toronto Street or King Street East. A single 1832 record refers to Toronto Street as “Dundas Street”.

It is probably reasonable to assume that the existence of a property with no access other than from a particular street suggests that that street was already present when the property first came into existence. In this way there is good evidence that the part of Ontario Street present in 1854 was also present by 1828 and that Church Street West was present by 1849. There are also a few cases in which a property fronting on Toronto Street had sides aligning on one of the other streets in Figure 6. Hence it looks likely that Church Street West was present by 1827, Robertson Street by 1844, and Cedar Street by 1849. However, this is somewhat weaker evidence because there is always the possibility that a street developed from a short laneway alongside a property rather than that the full street was present when the property was first purchased.

Figure 5. Streets on the Keeler Plan map (1854)

Percy Street is the one street in this part of Colborne for which land office records do provide some information. In 1833 Donald Campbell (ca. 1811-1892) purchased the property that now sits at the northwest corner of Church and Percy streets. In the record of this purchase the property’s eastern boundary was described as abutting on the Methodist Church “burying ground”. This means that Percy Street did not exist in 1830. It also means that at least part of the early cemetery for the church now lies under Percy Street. The first land purchase that definitively suggests the presence of Percy Street, because no other road access to the property existed, dates from 1851. Finally, on the 1854 Keeler Plan map Percy Street is labeled as “Percy Street, new graveled road”. No other street on the map is referred to as “new”, so Percy Street must have originated later than the rest of them. It probably dates from sometime around 1850.

From the fact that none of them are referred to as “new” on the Keeler Plan map, it seems reasonable to assume that all of the other streets illustrated had been present for some time. Joseph Abbott Keeler (1788-1855), who then owned all of the land north of King Street, started selling properties in the late 1820’s. Four properties were sold in 1827 and six in 1828. Three of these suggest that Ontario Street and Church Street West were present at the time (see above). The first use of the name “Colborne” in land purchase records dates to 1831. These facts combine to suggest that Keeler first came up with the idea of a town in the late 1820’s, or at least that he started to act on the idea at that time. Perhaps he laid out a series of streets then with that idea in mind.

Figure 6. Properties sold prior to the Keeler Plan (1854)

One of the Keeler Plan streets for which there is pretty good circumstantial evidence of origin is “lane” that would later be named Maybee Lane. It leads directly from King Street to the Keeler residence (now 9 Church Street East), supposedly built in 1820. It is pretty obvious that the street had its origin as the driveway for that house.

1856: The Grand Trunk Railroad

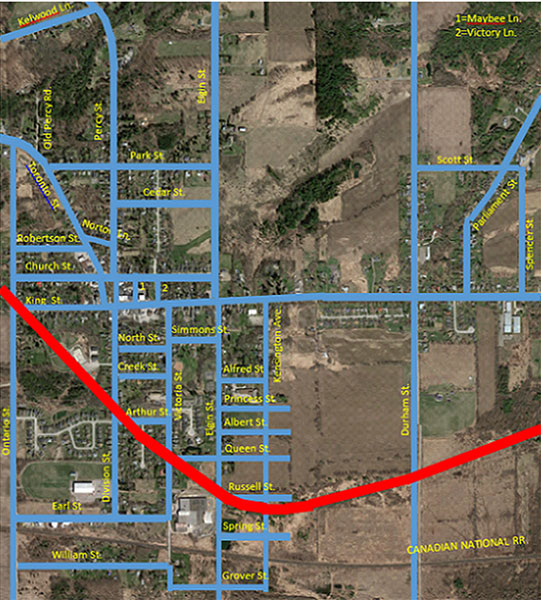

Until 1854 the southern part of Colborne was restricted to the row of properties along the south side of King Street. This changed with the opening of the Grand Trunk Railroad in 1856.

The town needed a more direct contact with the railroad station than along King Street West and Ontario Street, so Division Street was constructed in early 1858. This date can be pinpointed because land office records from 1857 refer to a planned road and after 1858 to an existing road.

The owners of the land immediately adjacent to the new railroad saw an opportunity, and laid out new land developments, complete with new road systems. Obviously they were hoping that the proximity of the railroad would attract buyers. This area is illustrated in Figure 7.

The land south of the railroad belonged to William Coulson (1808-1869). He had owned it since 1846 and from 1828 to 1846 it had been owned by Thomas Coulson (?-?; relationship unknown). The Coulson Plan map was produced in 1856 and included two streets running east-west between Ontario Street and Division Street (Coulson and William streets) and two streets running north-south (Henry and Thomas streets). Note that the name “Ontario Street” had by 1856 extended to include the “road to Colborne Harbour” on the 1854 Keeler Plan. Also note that Division Street was illustrated in the Coulson Plan, but other evidence (see above) suggests that it did not become a reality until early in 1858. This means that the Coulson Plan map showed a proposed development and not one that already existed.

Figure 7. Streets on the Coulson and “Bennett” Plans (1856).

Of the Coulson Plan streets (Coulson, Henry, Thomas, and William), only William Street still exists. One land purchase record from 1856 mentions Henry Street by name and properties bordering on Henry and Thomas streets continued to be sold into the 1890’s, so those streets apparently existed at one time as well. Coulson never sold a single property along Coulson Street and there is no hint of its existence on modern satellite photographs. However, it was illustrated in the 1878 Northumberland County Atlas so it apparently also had a brief existence.

The area north of the railway had been owned by Norman Bennett (ca. 1819-1872) since he inherited it from his father Festus Bennett (?-ca. 1851). Festus had owned it since 1821. There is no printed “Bennett Plan” map, but the area is designated as such in the 1878 Atlas and, like Coulson, Bennett undoubtedly established his development to try to take advantage of the new railway. He installed Bennett, Duke, and Earl streets running east-west, and Day Street was a continuation northward from Thomas Street of the Coulson Plan. Of these streets only Earl Street still exists. Bennett never sold any properties in his development except along Earl Street and the other streets eventually disappeared under the Colborne fairgrounds. The area is now occupied by the Keeler Centre.

1862: The Reid Plan

In 1862 James Hales Reid (1822-1899) surveyed Colborne and produced the Reid Plan map (Figure 8). The Reid Plan was used as the basis for all subsequent land transactions and is still important to land transaction records to the present.

The area north of King Street on the Reid Plan was little changed from the 1854 Keeler Plan map except that:

- Elgin Street was now present.

- The short street opposite Old Percy Road now had a name (Water Street).

- Park and Cedar streets now extended eastward to Elgin Street and the eastward extension of Cedar Street was called Baldwin Street.

The Reid Plan provided the earliest available map of East Colborne. In this area Durham Street and Furnace Road were illustrated, as were two small side streets off of Furnace Road: Mill Street and East Avenue.

Neither Mill Street nor East Avenue have survived to the present. Mill Street was named because it provided access to a saw mill owned by Titus Simeon Merriman (1806-1886). Merriman purchased this property in 1832, but it is unclear whether or not a saw mill and a road were present prior to his purchase.

Furnace Road became Parliament Street in 1893. The first reference to it in land records dates to 1833. The name refers to the iron foundry owned by Reuben Scott (1792-1862), who bought the property from Titus Merriman in 1832, just over a month after Merriman had acquired it. Like Merriman’s saw mill it is uncertain whether or not the foundry already existed at the time of Scott’s purchase. There is some indication in the James Pattison Cockburn (1777-1847) 1830 drawing of the Keeler Tavern that two roads ran into the background (northward) behind the tavern. The westernmost of the two would have been Furnace Road, so it was probably present by the late 1820’s. The Keeler Tavern dates to about 1816 but that doesn’t necessarily mean that Furnace Road was present at the time. The other road in the drawing appears to run northward just east of the tavern. No other record of such a road has been found. It may have been an alternative route to Scott’s foundry.

East Avenue ran along the backs of Reid Lots 202-205, all of which fronted on King Street. The first of these was purchased in 1837, but this may or may not suggest the presence of East Street at the time.

The origin of Durham Street is equally uncertain. As late as 1820 land records were referring to the road allowance rather than an actual road between Lots 28 and 29 of Concession 2, so no road was present at that time. There is a purchase record from 1843 for property with no road access other than Durham Street, so it apparently existed by then. Durham Street therefore came into existence sometime between 1820 and 1843.

South of King Street, the Reid Plan illustrated the streets laid out in the Coulson and Bennett Plans (discussed above). The name “Victoria Street” first appeared on this map for the “road to lake” illustrated on the Keeler map. Elgin and Durham streets also were illustrated for the first time. Elgin Street was not present in 1854, but the Keeler map did not cover the East Colborne area so it provided no information about Durham Street. There were land transactions for properties for which no other road access existed other than Durham Street as early as 1802, so the part of Durham Street running south from King Street may have been one of the very first roads in the area.

A series of east-west roads between Division and Victoria streets were also illustrated on the Reid Plan map. From north to south these were North, Creek, Vale, Ark, Alice, and Clare streets. Only North and Creek streets exist today. Of the others, only Vale Street was illustrated in the Park Lot Plan of 1873 or the 1878 Northumberland County Atlas. However, an 1877 land record refers to a “strip of land known as Vale Street on the Reid Plan but not yet opened up”. This suggests that these streets on the Reid Plan were anticipated rather than actual streets. They probably never actually existed.

Figure 8. Streets on the Reid Plan map (1862)

1864: The Grover Plan

John Merriam Grover (ca. 1815-1888) developed the land south of King Street and east of Elgin Street in 1864. As part of his plan he laid out a series of streets. One of these, Kensington Street, ran north-south and the remainder (Monck, Alfred, Princess, Albert, Queen, Russell, Spring, Grover, and Napier) ran east-west (see Figure 9). Queen and Grover streets extended westward to Victoria Street. All of these streets appear in the 1878 Atlas and on the 1889 Glebe Plan (see below), so they all existed. The only ones that remain to the present are Kensington Avenue and Alfred Street. Kensington Avenue exists in a much truncated from, extending southward only as far as Alfred Street. Everything in Grover’s development south of Alfred Street, with the exception of the Colborne Public School, is now empty land.

Figure 9. Streets on the Grover Plan (1864)

1873: The Park Lot Plan

There are actually two plans dated 1873 that divided the area between Division and Victoria streets and south of Creek Street into units referred to as the Park Lots. One of these plans covered the entire area and showed only Vale Street. As discussed above, however, Vale Street was not a reality as of 1877 and may never have existed at all as a functioning street. It does not exist on an aerial photograph from 1920 (see below). The other plan focused on Park Lot L. It illustrated Vale Street as well as a street to the south, which it labeled Arthur Street. Arthur Street still exists.

1876: The Scott-Spencer Plan

Reuben Bartlett Scott (1826-1899, son of the Reuben Scott mentioned above) and Hiram Spencer (1806-1892) produced a development plan for East Colborne in 1876. It showed Durham Street, Furnace Road, and East Avenue (discussed above). Mill Street by this time had disappeared. Two new streets made their first appearance on this plan: Scott Street and Spencer Street. Both still exist. See Figure 10.

Figure 10. Streets on the Scott-Spencer Plan (1876).

1878: The Northumberland County Atlas

Unlike the plan maps discussed to this point, the Northumberland County Atlas recorded the streets that actually existed in 1878 and did not present plans for the development of new ones. Everything illustrated in the atlas has already been discussed with one minor modification: “Baldwin Street” on the 1862 Reid Plan map was now referred to as part of Cedar Street.

1889: The Glebe Plan

Lot 31 of Concession 1, the area bounded on the north by King Street, on the west by Victoria Street, and on the east by Elgin Street, was originally a Clergy Reserve and its eastern half was glebe land serving the Anglican Church until it was subdivided and sold off in 1889. The Glebe Plan map that year illustrated one new street for the first time: Simmons Street just south of King Street (Figure 11). A bylaw opening this street was passed in 1877 and its first appearance in land records was in 1882. It still exists.

Figure 11. Streets on the Glebe Plan map (1889)

1906: The Extension of Church Street East

Before 1906, Church Street East extended eastward only to Victory Lane. It now extends to Elgin Street. The hypothesis that the Church Street extension went into use in 1906 is based on the following reasoning: The Corporation of Colborne purchased land on Elgin Street from Lucy Jane Goslee (1837-1919) in 1902 for the express purpose of extending Church Street, so the extension couldn’t have been present earlier than that. Further, between 1902 and 1906 land transaction descriptions referred to measurements taken from “Church Street produced eastward to Elgin Street”, meaning from an imaginary line drawn eastward from Church Street as it then existed. If the extension had been present when they were written, these descriptions would have made reference simply to “Church Street”, not to “Church Street produced eastward”. On the other hand, there was a flurry of transactions involving land east of Victory Lane in 1906 that referred to measurements taken from simply “Church Street”. Records referring to “Church Street produced eastward” continued until 1915, but after 1906 they were word-for- word copies of earlier land descriptions.

1910: The Canadian Northern Ontario Railroad

The Canadian Northern Ontario Railway Company was incorporated in 1899 and from 1905 on the company purchased land for a new right-of-way across Canada. These purchases included several in the Colborne area, all made in 1910. Service between Toronto and Trenton started in 1911, but the CNOR was a financial failure and the government took it over and combined it, along with several other railways, including the Grand Trunk, into the Canadian National Railway Company (CN) in 1917. The Canadian Northern line was abandoned shortly after the takeover, but the remains of its earthworks are easily visible on satellite photographs to this day. Its route through Colborne is illustrated in Figure 12.

The CNOR interfered with traffic on nine Colborne Streets. Functional street crossings were installed on Ontario, King, Division, Arthur, and Victoria streets, but the construction of the railroad probably marked the demise of the section of Queen Street west of Elgin, and the parts of Elgin Street and the Grover development streets south of the track (Russell and Spring). The purchase record by the CNOR of the right of way through the Grover development states that:

“The Grantor shall have a level crossing where the cut and fill meet, and upon the further understanding and agreement by and between the parties hereto that, as the public road to the west side of the above described property is not opened to the south of the railway, the grantor shall take the risk of having to open the same.”

The road referred to is Elgin Street. Since this street now ends at the point where the CNOR once crossed it, it looks like the Grantor never bothered to extend access to the south. The Grantor was Daniel Lewis Simmons (1830-1915), who owned all of the Grover property south of the track. Street access was not needed to reach anyone else’s property.

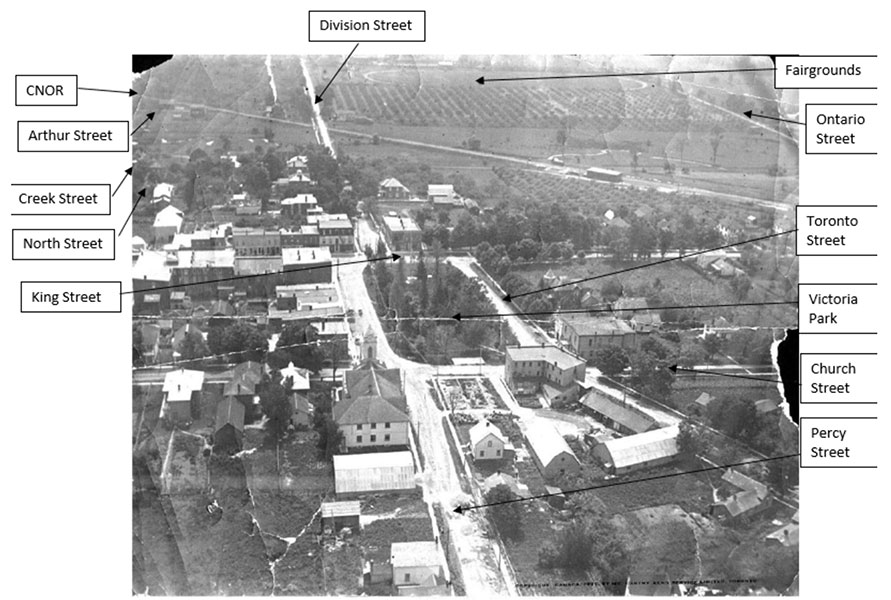

1920: Aerial Photographs

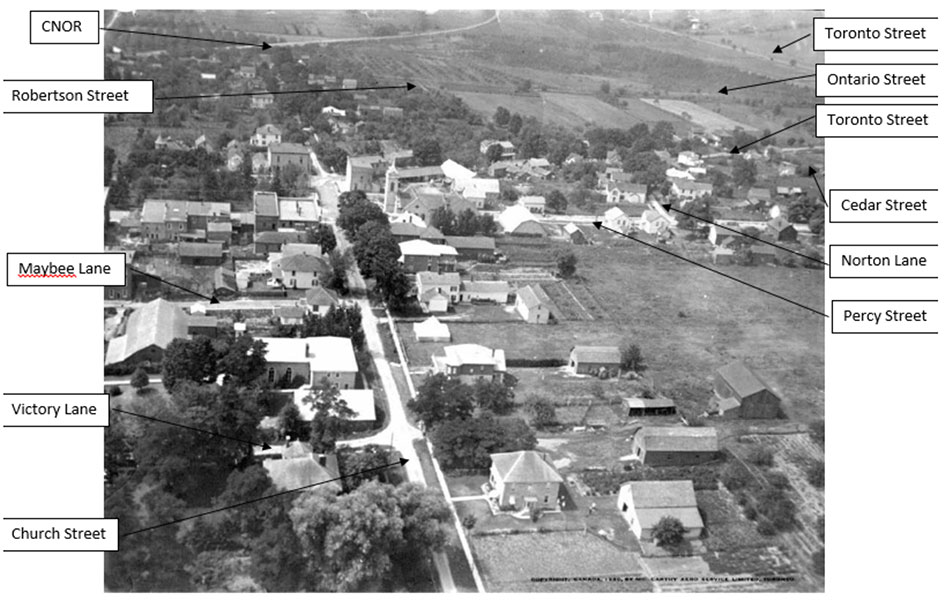

Two aerial photographs from 1920 exist, one looking south along Division Street (Figure 13) and the other looking west along Church Street (Figure 14). Unlike the available historical maps of Colborne, these photographs provide incontrovertible evidence for the presence or absence in 1920 of the streets in their fields of view.

Church Street, Division Street, Earl Street, King Street, Ontario Street, Percy Street, and Toronto Street are clearly visible in Figure 13. The Canadian Northern Ontario railway right-of-way is also evident cutting diagonally across the image. Creek Street can be seen peeking through the trees to the left of Division Street. Although the streets themselves can’t be seen, there are buildings in the photograph that show the positions of North and Arthur streets. It is also apparent that none of the other historical streets south of Creek Street (Vale, Ark, Alice, and Clare) existed in 1920. The Bennett Plan streets (Bennett, Duke, and Day) are also absent, there being an oval track in the upper right part of the picture where they once existed. This was the Colborne Fairground (later the site of the Keeler Centre).

Figure 14 shows Cedar Street, Church Street, Maybee Lane, Norton Lane, Ontario Street, Percy Street, Robertson Street, Toronto Street, and Victory Lane. It also shows that the part of Norton Lane east of Percy Street did not exist in 1920.

Figure 12. Route of the Canadian Northern Ontario Railway

Figure 13. 1920 aerial photograph looking south along Percy and Division streets.

Other Streets

The only streets illustrated in Figure 1 that have not yet been discussed are Burnham Street, Cortland Crescent, Janes Court, Keeler Court, Kelwood Lane, Rotary Centennial Park Drive, Streamside Drive, and Thornlea Street. Of these only Kelwood Lane was present prior to the 20th Century. Unfortunately it doesn’t appear on any of the historical maps of Colborne other than the 1878 Atlas. Land records involving this street date to 1832 and in early records it is generally referred to as “the road to Ozem Strong’s house”. One record from 1851 referred to it as the “road to Grafton”, so apparently it extended west beyond where it ends today.

The Burnham Street development dates to 1949, Streamside Drive and Thornlea Street to 1969, Rotary Centennial Park Drive (formerly Arena Drive) to 1970, Keeler Court to 1989, Jane’s Court to 2004, and Cortland Crescent to 2005.

Historical Colborne Streets that No Longer Exist

Alice Street.—As discussed above, this street probably never actually existed.

Albert Street.—By 1904 everything south of Alfred Street in the Grover Plan development belonged to either Daniel Lewis Simmons (1830-1915) or Albert Elnathan Mallory (1848-1904). After that time no properties required any of the Plan’s other streets (Princess, Albert, Queen, Russell, or Spring) for access, so they probably went into disuse at that time. Interestingly, a bylaw passed in 1954 stated that the Grover Plan “subdivided a part of said township lot 30 into Village lots and made allowance for streets as named thereon but to this date only Alfred Street and the northern part of Kensington Street have been

Figure 14. 1920 aerial photograph looking west along Church Street.

opened and used” and that “all other streets shown on said plan have been and still remain a part of farm lands and unopened.” In other words, according to this bylaw none of the streets south of Alfred Street ever existed. This seems unlikely because there are numerous land purchase records that make reference to these streets. If these had all been purchases in 1864-1865 they might have been bought as speculation in the hopes of the subdivision and its streets becoming viable, but they continued for more than 30 years after that, so it seems more likely that the streets actually existed. They exist in the 1878 Atlas. To obscure things even more, there is a bylaw dated 1892 (text not seen) that apparently opened Albert, Elgin, Kensington, and Queen streets and another (also not seen) supposedly opening Princess Street in 1894. Both of these appeared long after many of the land records involving these streets. How could they have been opened at such a late date? Could it be that the streets existed in an unofficial capacity until they were recognized as the responsibility of the town in 1892-1894? This is very confusing.

Ark Street.—As discussed above, this street probably never actually existed.

Bennett Street.—Bennett, Duke, Earl, and Day Streets were laid out in the Bennett development plan of about 1856. Of these, only Earl Street still exists. The other streets appear in the 1878 Atlas. They also appear on the 1934 insurance map, but the fact that they are absent from the 1920 aerial photograph proves that the 1934 map was not accurate. The streets therefore disappeared sometime between 1878 and 1920. The Bennetts never sold any lots in their development and the property remained in the family until it was sold to the Colborne Athletic and Driving Park Associates in 1895. This association probably installed the oval track visible in the 1920 photograph on the site of the Bennett development streets. This narrows down the demise of Bennett, Duke, and Day streets to between 1878 and 1895. The best working hypothesis is that they existed in some form until they were destroyed for the driving park in 1895. The Bennetts owned this entire area, so the streets probably only amounted to lanes dividing up their land (likely used for orchards) before that.

Cedar Street between Percy Street and Ontario Street.—A bylaw officially eliminating the part of Cedar Street between Ontario and Toronto Streets was passed in 1947. It states that “said parcel was never at any time accepted by the Municipality of the Village of Colborne as a street or public thoroughfare, but has always remained in the possession and ownership of the original owners and their heirs and assigns”. This is despite the fact that it this section of street appeared in the Keeler and Reid Plans as well as in the 1878 Atlas. Properties flanking the part of Cedar Street between Toronto and Percy Streets continued to be sold at least through 1952.

Cedar Street between Burnham and Elgin Streets.—This street was present on the 1878 Atlas map and on the 1934 insurance map, although the latter is of questionable accuracy. It definitely was gone by the time the Burnham Street plan was produced in 1949. Official closure by bylaw didn’t happen until 1979.

Coulson Street.—William Coulson (1808-1869) laid out the Coulson Plan in 1856 and managed to sell several lots along Henry, Thomas, and William streets, but none were ever sold along Coulson Street. Everything along both sides of Coulson Street remained under single ownership so there is no evidence one way or the other regarding whether the street ever existed. If it did, it probably didn’t exist for very long.

Clare Street.—As discussed above, this street probably never actually existed.

Day Street.—See discussion under Bennett Street above.

Division Street south of Earl Street.—The Coulson Plan of 1856 showed Division Street extending southward as far as Coulson Street, south of the Grand Trunk tracks. However, Division Street did not yet exist when that plan was drawn up, and it may be that the true southern end of Division Street was the access to the railway station just south of Earl Street. Division Street as portrayed on the Coulson Plan may never have existed. The land was definitely under private ownership by 1936.

Duke Street.—See discussion under Bennett Street above.

East Avenue.—This street appears on the 1862 Reid Plan and the 1876 Scott-Spencer Plan. It is also illustrated, but not named, in the 1878 Atlas. It was absent from the 1934 insurance map. It was officially closed by bylaw in 1956.

Elgin Street between Park and Church Streets.—There is currently a gap in Elgin Street here. Unfortunately, there are very few historical maps of this area. The section of street appears in the 1878 Atlas. It also appears on the 1934 insurance map, but that map is known to include other roads that are were actually absent by 1934, so it is unclear whether or not this corresponds to reality.

Elgin Street south of the Canadian Northern Ontario Railway.—As discussed above, the southern part of Elgin Street went out of commission when the CNOR was constructed in 1910-1911.

Grover Street.—All of the Grover Plan land south of the Grand Trunk Railroad was owned by Daniel Lewis Simmons (1830-1915) by 1905 so Grover and Napier streets were probably little used after that time. A land purchase record from 1912 includes a map that suggests that Napier Street was still present, but Grover Street was absent.

Henry Street.—See discussion under Coulson Street above. All of the properties along Henry and Thomas streets ended up in the hands of a single owner, Mary Emily Isabel McTavish (1847-1932), by 1892. They probably started to fade from existence at about that time. McTavish, by the way, was the daughter of Maria Louisa Simpson (1815-1891) and therefore the granddaughter of Hudson Bay Company mogul George Simpson (1786-1860).

Kensington Street south of Alfred Street.—See discussions under Albert Street.

Mill Street.—Appears on the Reid Plan map of 1862 but not the Scott-Simmons Plan map of 1876. The disappearance of the road can’t be narrowed down any further than that.

Monck Street.—Part of the Grover Plan of 1864, this street was absent by 1934. The last property that required Monck Street for access was sold in 1892 and combined with adjoining properties. Monck Street probably went out of use at about this time.

Napier Street.—See discussion under Grover Street above.

Norton Lane east of Percy Street.—A bylaw officially decommissioning this bit of street was enacted in 1974, but as a functional street it had disappeared long before. It was present in the 1878 Atlas but absent from the 1920 aerial photograph (see above). When it went into disuse is uncertain. The final pre-1920 land purchase for a lot adjoining Norton Lane was in 1919, but this lot fronted on Toronto Street so it doesn’t provide any evidence for or against the viability of Norton Lane.

Old Percy Road between end of current cul-de-sac and Percy Street.—Before the opening of Percy Street probably sometime around 1850, Old Percy Road was the main route northward to Castleton and beyond. Most of the section between Toronto Street and Percy Street went out of service in 1886, leaving the current cul-de-sac still bearing the name.

Princess Street.—See discussion under Albert Street above. Bylaws officially decommissioning parts of the street were passed in 1954 and 1970 but it had probably been long disused by that time.

Queen Street.—See discussion under Albert Street above for the part of Queen Street east of Elgin. The part of Queen Street west of Elgin went out of commission when it was blocked by the construction of the Canadian Northern Ontario Railway in 1910/1911. It was not officially closed by bylaw until 1966.

Russell Street.—All of the land on both sides of Russell Street (and everything from there south to the Grand Trunk Railway) belonged to Daniel Lewis Simmons (1830-1915) by 1892. This probably marked the beginning of the end for Russell and Spring streets. The last nail in coffin for Russell Street may have come when it was blocked by the construction of the Canadian Northern Ontario Railway in 1910/1911. Russell, Spring, and the southern part of Kensington were closed by bylaw in 1969.

Spring Street.—See discussion under Russell Street above.

Thomas Street.—See discussion under Henry Street above.

Vale Street.—As discussed above, this street probably never actually existed.

Water Street.—This is a short section of street near the junction of Ontario and Toronto Streets (across Toronto Street from Old Percy Road). It appears on the Keeler Plan of 1854, the Reid Plan of 1862, and the 1878 Atlas. It also appears on 1934 insurance map, but, as discussed above, this is not clear-cut evidence that it actually existed in 1934. No land record examined has made any reference to the street. There is a good chance it was gone by 1881 because there was a land sale that year that included all of the property on both sides of the street. A bylaw officially eliminating the street was passed in 1976.

Origins of Colborne Street Names

Albert Street.—Of the streets laid out by Grover in his development plan of 1864, all but one were named after public figures of the day. “Albert” was the Prince Consort, husband of Queen Victoria, who had died in 1861, or perhaps her eldest son Albert Edward (1841-1910) who would eventually become King Edward VII but was 23 years old in 1864. Among the other streets in the development was one named after Victoria’s second son Alfred and another probably in honour of one or more of her daughters, Princess Street. So perhaps the Prince of Wales was the more likely honoree.

Alfred Street.—See discussion under Albert Street above. Alfred Street is probably named after Queen Victoria’s second son, Alfred the Duke of Edinburgh and Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha (1844-1900).

Alice Street.—The identity of “Alice” is uncertain. Two of the Reid Plan streets proposed for the area between Division and Victoria streets and north of the railway were “Alice” and “Clare” streets. This might suggest that they were someone’s daughters. It is possible they were Clara (1845-1909) and Alice (1850-1914), daugthers of Allan Taylor Maybee (1812-1886), a prominent Colborne businessman of the day (and after whom Maybee Lane is named). They were the only two of this daughters who were still alive and as yet unmarried at the time.

Ark Street.—The only “Ark” that comes to mind is the one of biblical fame.

Arthur Street.—The identity of “Arthur” is unclear. No record has been seen of a Colborne resident of the era by that last name and, although there were numerous people with the first name Arthur, none of them seems to be obviously associated with the Park Lots. It could be named after Sir George Arthur (1784-1854), a former lieutenant governor of Upper Canada, but he had been dead for 20 years. Or perhaps it might have simply been named after King Arthur.

Baldwin Street.—Named after Robert Baldwin (1804-1858), Premier of Upper Canada from 1843 to 1848 and a proponent of political reform. His Baldwin Act of 1849 made municipal government truly democratic rather than an extension of central control by the Crown.

Bennett Street.—This street was probably opened in about 1856 as part of Norman Bennett’s attempt to cash in on the presence of a new railway station just to the south. It was named after Bennett himself (1819-1872), or perhaps after his father Festus Bennett (?-1851).

Cedar Street.—Undoubtedly named after the common local conifer.

Church Street.—This street runs in front of the Methodist Church and behind the Presbyterian Church.

Clare Street.—See discussion under Alice Street.

Coulson Street.—This street was named after William Coulson (1808-1869), in whose land development it was located.

Creek Street.—Keeler’s Creek runs along the backs of the properties on the south side of Creek Street.

Day Street.—This street may have been named after day, the opposite of night. Alternatively there were a few people named Day who were residents of Colborne in the 1850’s and the street might have after one of them. Interestingly, the maiden name of Joseph Abbott Keeler’s wife Nancy (1790-1858) was Day. Her relationship to other Colborne Days remains obscure.

Division Street.—Division Street lies on the dividing line between Lots 31 and 32 of Concession 1, or, in 1858 terms, between the lands of Norman Bennett (1819-1872) and Joseph Keeler (1824-1888) , two of the major Colborne landholders at the time.

Duke Street.—“Duke” might refer to a surname or it might refer to “Duke” the aristocratic title. Since the Bennett Plan street immediately to the south was Earl Street, it would appear that the latter was the case. No Colborne resident named Duke has been found.

Durham Road.—This road was named either after the English city and county of Durham or after John George Lambton (1792-1840), the Earl of Durham, who came to North America to investigate the causes of the 1838 rebellions in Upper and Lower Canada, and who’s report was instrumental in bringing about the union of the two colonies into a single Province of Canada in 1841.

Earl Street.—See discussion under Duke Street above. “Earl” refers to the aristocratic title, and not to a surname, even though there was a family named Earl living in Colborne in the 1850’s.

East Avenue.—This street ran eastward from Furnace Road. This seems like a pretty weak reason to name a street, there being plenty of other streets running eastward from other streets, but no other source of the name is apparent.

Elgin Street.—James Bruce (1811-1863), 8th Earl of Elgin and 12th Earl of Kincardine, was Governor General of Canada from 1847 to 1854. He was also the Governor of Jamaica from 1842 to 1846 and the Viceroy of India from 1862 to 1863.

Furnace Road.—This was an earlier name for Parliament Street. It was so named because it ran by an iron foundry owned by Reuben Scott (1792-1872).

Grover Street.—This was one of the streets in the land development plan laid out by John Merriam Grover (ca. 1815-1888) and was named after Grover himself.

Henry Street.—The streets in the Coulson Plan were Coulson, Henry, Thomas, and William. The origin of the street name “Coulson” is obvious. The other three streets had the same names as the developer William Coulson’s three eldest sons, William A. (1840-1880), Thomas Adkinson (1841-1906), and Henry B. (1843-?).

Kensington Street.—Kensington is an affluent district in West London and the site of Kensington Garden.

King Street.—The first record available for the use of this name is on the Keeler Plan map of 1854, but the name could easily date from some earlier time. In land records even after 1854 it was generally referred to as the Kingston Road, the York (or Toronto) Road, or, most commonly, the Main Post Road. There is no record of a particularly significant Colborne resident named King dating from in or before the 1850’s, so the origin of the name would seem most likely to have been with reference to the King of England. There was no King of England after the accession of Queen Victoria in 1837 until her death in 1901, so the name would have to have been pre-Victorian. The street follows the course of the Danforth road, finished in 1799, so the King could have been George III (reigned 1760-1820), George IV (1820-1830), or William IV (1830-1837). There is some evidence that the village of Colborne came into existence in the late 1820’s, so perhaps George IV is the most likely candidate.

Maybee Lane.—Allen Taylor Maybee (1812-1886) was a prominent Colborne businessman who owned properties in downtown Colborne, including along Maybee Lane.

Mill Street.—Named because it ran by a saw mill owned by Titus Simeon Merriman (1806-1886) beginning in the early 1830’s. It may have dated from some time earlier as well.

Monck Street.—Of the streets laid out by Grover in his development plan, all but one were named after public figures of the day. Charles Monck (1819-1894) was the Lieutenant General of both Upper and Lower Canada from 1861 to 1867. After Confederation he became the first Governor General of Canada, but this was after Monck Street in Colborne had been named after him.

Napier Street.—This was another of the Grover Plan streets that were probably named after important public figures. The most prominent Napier of the day seems to have been Charles James Napier (1782-1853), among other things commander-in-chief of the British forces in India.

North Street.—This street may have been named after Frederick, Lord North (1732-1792), British Prime Minister at the time of the American Revolution, or it may simply have been named because it was the northernmost of the streets that were constructed (or at least planned) south of King Street and between Division and Victoria streets in the late 1850’s.

Norton Lane.—No records have been found of a Colborne resident named Norton. There was a Hiram Norton (1799-1875) who ran a stagecoach line between Toronto and Montreal (and hence through Colborne) in the 1830s. Was Norton Lane named after him?

Office Lane.—This was a prior name for Victory Lane. “Office” refers to the Land Registry Office which had been built at the corner of this street and King Street shortly before the production of the Reid Plan, on which the name “Office Lane” first appeared.

Old Percy Road.—Percy Road and later Percy Street were so called because they led to Percy Township which in turn was named in 1798 in honour of Lady Elizabeth Seymour (1716-1776), wife of Hugh Percy (1714-1786), first Duke of Northumberland.

Ontario Street.—Obviously named after the province of Ontario.

Parliament Street.—This street was either named after parliament, the government institution, or after Colborne businessman Henry Jason Parliament (1844-1943).

Park Street.—No reference to a Colborne resident named Park has been found, although there was a John Park (ca. 1801-?) who appeared in the 1851 Cramahe census and who owned property in Concession 9 in 1861. It is not known if Park Street was named after him. In fact, it is probably doubtful. “Park” may not even refer to a person.

Percy Street.—See discussion under Old Percy Road above.

Princess Street.—Most of the streets in John M. Grover’s development plan were named after prominent public figures of the day. Two of them probably honoured two of Queen Victoria’s sons and “Princess” likely honoured one or more of her daughters. Alternatively, Grover had four daughters in their teens and early twenties in 1864 and it is just possible that Grover referred to one or more of them as “princess”.

Queen Street.—Named in honour of Queen Victoria (1819-1901). The road didn’t exist before 1864, so it couldn’t have been named after the wife of one of Britains earlier Kings.

Robertson Street.—Robertson Street was undoubtedly named after Donald Robertson (1806-1877) who owned several properties on both sides of Toronto Street at or near its junction with Robertson Street. These properties were purchased between 1835 and 1847 (others were purchased later in the 1850’s, after the Keeler Plan). For most of his career Robertson ran a general store.

Russell Street.—Most of the streets in John M. Grover’s development were named after prominent public figures. John Russell (1792-1878) was the British Prime Minister from 1865 to 1866 and before that he had been Secretary of State for the Colonies (1855) and Foreign Secretary (1859-1865).

Scott Street.—Reuben Bartlett Scott (1826-1899) and Hiram Spencer (1806-1892) produced a development plan for East Colborne in 1876. They named Scott Street and Spencer Street after themselves.

Spencer Street.—See discussion under Scott Street above.

Spring Street.—This was the only one of the streets in the Grover Plan that does not appear to have been named after a public figure. It probably refers to a natural feature. Two ponds exist now where the west end of Spring Street used to lie. They may suggest a natural source of water.

Thomas Street.—See discussion under Henry Street above.

Toronto Street.—So named because it leads from Colborne to Toronto. The latter name was officially substituted for “York” in 1834.

Vale Street.—This street may have been named after someone named Vale or it may have been named after a topographic feature. Unfortunately, neither alternative seems particularly convincing. No reference to a Colborne resident or a public figure named Vale has been found, and it is hard to understand how anyone would see a geographic feature in this area (between the modern Creek and Arthur streets) that they would refer to as a vale.

Victoria Street.—Probably named in honour of Queen Victoria (1819-1901).

Victory Lane.—Clearly refers to some popular British Victory since 1862, at which time the street was referred to as “Office Lane”. The name Victory Lane appears on the 1934 insurance map, so the “victory” was clearly not World War II. Although there were numerous smaller victories in that period, by far the most likely one to have called for renaming a street in Colborne was World War I.

Water Street.—The origin of this name is obscure. There doesn’t appear to have been any early Colborne resident named Water and there are no streams in the area. Perhaps there was a well or spring.

William Street.— See discussion under Henry Street above.

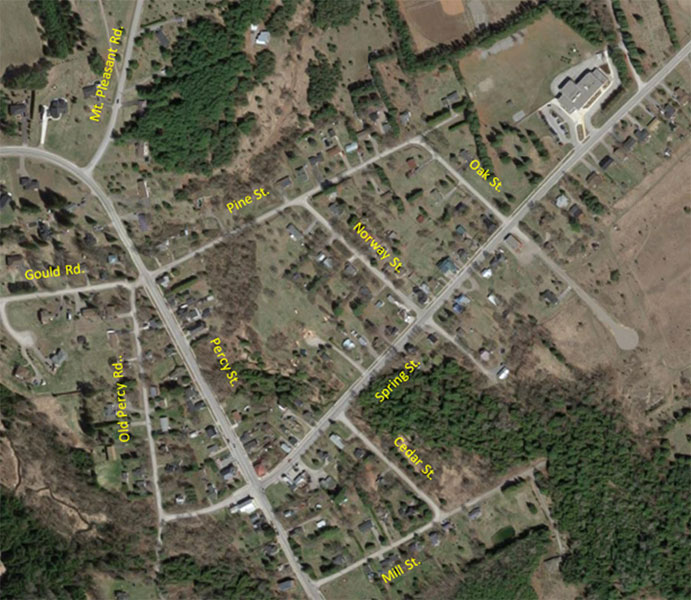

The Streets of Castleton

Figure 1 illustrates the streets as they now exist. The 1854 streets (Figure 2) were similar except:

Figure 1. Modern Castleton streets.

1. Norway Street extended southeastward and Mill Street northeastward far enough to meet each other.

2. Old Percy Street extended northward to cross Percy Street and joint Mount Pleasant Road. The modern junction of Mount Pleasant Road and Hwy 22 did not exist.

3. Gould Road was called the Haldimand Road.

4. Pine Street extended eastward across what is now the back of the Public School property as far as the cemetery.

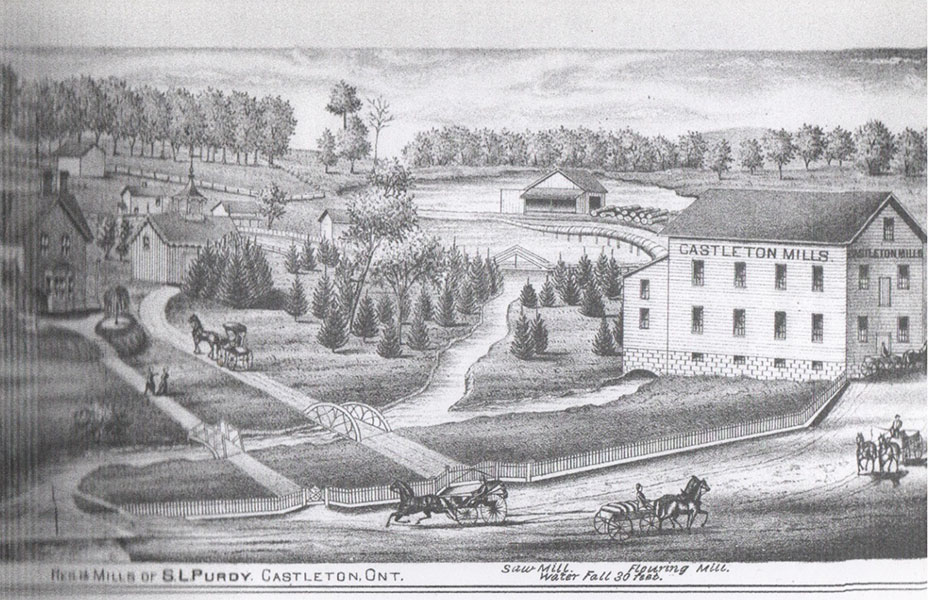

5. A short section of street extended between Plan 57 lots 97 and 98 to connect Percy Street opposite Mill Street with the midpoint of the section of Spring Street between Percy Street and Old Percy Road. This section of street was not named on the Plan 57 map. The illustration of the Purdy residence and mill from the 1878 Atlas (Figure 3) actually corroborates the presence of this short street. This illustration is drawn from the vantage point of the arrow in Figure 2. Notice the wagon tracks in the lower right-hand corner of the illustration. People travelling from left to right along the road in the foreground of the picture had the choice of continuing straight ahead or veering to the left to pass in front of the mill. Straight ahead took them up Percy Street. The left turn took them up this no longer extant street.

Figure 2. Plan 57 streets (1854)

Castleton Before 1854

The Keelers are supposed to have built a mill at the site of Castleton as early as 1806. This mill would have needed a road to transport its products to Colborne and points beyond. This probably followed more-or-less the route of Old Percy Road and modern Highway 25.

There was no Castleton in 1806. In fact all of the land in the southern halves of Concession 7, Lots 32-34, now occupied by Castleton, belonged solely to the Keelers until 1848 and only three properties were purchased from them before the production of Joseph Keeler’s plan in 1854. These were:

1. The hotel (variously later called the Castleton Hotel, Temperance Hotel Oriental Hotel, and Union Hotel) at the northeastern corner of what is now Percy and Spring Street sold in 1848.

2. The lot immediately south of the hotel across Spring Street at the southeastern corner of Percy and Spring streets sold in 1852.

3. A property on the east side of Percy Street a bit north of the Castleton Hotel sold in 1852.

The 1854 Keeler plan predated all other land sales in the Castleton area. However, land office records provide evidence that a settlement was present before that date. First, there was a hotel present by 1848, and probably before. Second, the lot at the southeastern corner of Percy and Spring streets was already occupied by a “merchant shop” by the time it was sold in 1852. Third, the sales record for the lot north of the Castleton hotel referred to it as being opposite “Campbell’s cooper shop lot”. Climo (1988) suggests that the community dates back considerably farther:

“The area around Castleton began to get populated after 1806, when Joseph Keeler built his mill here. It soon afterward became a stop on the Methodist missionary circuit. The first name of Castleton was Piper’s Corners, probably named after one of the early settler families. The stream that runs through English Hollow was called Piper’s Creek. For a while, the village was also called “Centreville”, but because the village of Centreton was so close by, and because “Centre” was used in names of many settlements, the residents of this village held a meeting to choose a new name for it. They decided on “Castleton”, which was the name of a town in England as well as a town in Vermont, U.S., where some of Joseph Keeler’s original settlers had come from.”

Figure 3. 1878 illustration of Purdy residence and mill

Unfortunately, Climo provides neither evidence for the events he cites, nor the dates on which they occurred.

As far as Castleton streets go, the 1854 Keeler plan provides the first evidence for all except four of them:

1, As already mentioned, there was probably a road running south to Colborne by about 1806.

2,3. Land office records from 1848 and 1852 refer to the presence of “New Percy Street”. This, of

course, means that Old Percy Road must already have been present for some time.

4. The properties along the eastern side of Percy Street flanking Spring Street were both present in

1848/1852, so Spring Street must have been there as well.

This brings up another interesting point. For many years the road from Colborne to Warkworth followed what was called the “Cramahe Graveled Road”, which came up Percy Street and turned right onto Spring Street. This is still the route of Highway 25. As in Colborne, Percy Street was so named because it led to Percy Township, as the township north of Cramahe was then called. But Percy Street, and Old Percy Road extend north of the intersection with Spring Street. This means that the main route to Percy Township must have originally continued northward rather than turning onto Spring Street. If one looks at a map of Cramahe Township, it is clear that this route would have followed what is now Mount Pleasant Road to Morganston Road, then east to Morganston before turning north again to Warkworth in Percy Township (Figure 4). Or it might have bypassed Morganston to the west and followed what are now Campbell and Cliff roads north from Morganston Road.

Castleton After 1854

When did the main route to Percy Township shift from Percy Street to Spring Street? The only solid bit of evidence was the sale in 1876 of the part of Old Percy Road in the northern part of Castleton between Percy Street and Mount Pleasant Road. The section of road was referred to as closed at that time. Somewhat weaker evidence is seen in the fact that Spring Street was called the “road to Jones’s” or “Jones Road” in the earliest land records (1848, 1852, 1855). This is a reference to the Jones family who settled east of Castleton in Lots 23-26 of Concession 7, beginning with the purchase of Lot 26 by John Jones (ca. 1801-?) in 1835. This suggests that the extension of Spring Street east from Castleton did not extend to Morganston and Percy Township at that time. If it had, one of those places would probably have been used as a reference point in the name. The first reference found for this road as the “Percy graveled road” was in a land record from 1864. This puts the most likely time for the shift in the main road northward sometime between the early 1850’s and 1864.

All of the other streets in Castleton were present on Keeler’s plan for the town in 1854. Such plans, however, are often just that: plans for roads rather than maps of roads that actually existed. Land purchases that demonstrate the existence of Castleton Roads are as follows. Bear in mind that any of them could easily have been present earlier.

Cedar Street.—1859

Haldimand Road (later Gould Road).—1857

Mill Street.—1861

Norway Street.—1854

Oak Street.—1860

Old Percy Road.—1854, but certainly present earlier

Percy Street.—1848, but certainly present earlier

Pine Street.—1857

Spring Street.—1848, but certainly present earlier

Figure 4. Historical routes to Percy Township

Castleton Street Names

Percy Street and Old Percy Road are so called because they led to Percy Township. Haldimand Road led to Haldimand Township. Its later name, Gould Road, is in honour of a prominent Castleton family. Mill Street refers to the Purdy Mill just opposite its western terminus. Cedar, Oak, and Pine streets refer to common trees in the area. Norway Street is a bit obscure because there is no particular historical connection with Norway. Given that several other Castleton streets are named after trees, is it possible this is a reference to the Norway spruce, an extremely popular planted tree in the 19th Century? This leaves Spring Street. Was it named after the season, or was there a water source somewhere along the street at some point? Its former name, Jones Road, was a reference to the Jones family, as discussed above.